A death-blow is a life-blow to some;

Who, until they died, did not alive become;

Who, had they lived, had died,

But when they died, vitality begun.

—Emily Dickinson

And here’s another ghost story I can tell you:

Elizabeth has been dead for years when she takes her first spin in a motor-buggy. She never did so when alive, and when she once refused a chance, her husband assumed her too fearful to try. He was right, and he was wrong. There are many varieties of fear. Elizabeth had worried that, if she took a seat beside the driver, soon she wouldn't care less if her hat flew off and she shouted “Faster,” exposing a part of her mind she wished to hold secret.

Now, Elizabeth is invisible to the living and indifferent to their opinions. On a whim she floats to a passing motor-buggy, an old-fashioned one by now—with no roof, it’s only good for traveling in the best weather. She settles behind the driver and takes in the increasingly disappointing experience. The buggy rattles, the engine groans—or perhaps a better word would be growls—and, worse, the driver keeps to familiar thoroughfares. The constraint of this fashion of travel resembles too much her former life’s constraints, and there’s no point insisting “Turn here” in her ghostly voice that the driver won’t hear. Elizabeth lifts in the air without regret. She can dart down any street she wishes and fly with greater speed.

The narrow street she chooses curves to a quiet corner. There, a boy scrapes a fragment of charcoal against the sidewalk. He draws a face—or rather he draws a third face, having already completed two others. He bends over a puddle, a remnant of yesterday’s storm, examines his reflection, and then returns to his art. Elizabeth settles in the air beside him to follow his progress. He has captured easily enough his unruly hair and thin eyebrows, the slightly crooked nose—had it once been broken?—and the soft line of his jaw. But his eyes. This precocious child’s charcoal is no match for them. Those eyes have undone every portrait and forced him to start again. His emotions reflected there are too fluid to find a single resting place, no single attempt would tell the truth of him. He doesn’t yet realize this. He begins a fourth self-portrait.

Perhaps his persistence is stubborn labor, not struggling insight.

Elizabeth is willing to wait and see. The way he worries his shrinking piece of charcoal, she believes a part of the boy knows he has to keep searching, even if he doesn’t yet know what he searches for. Something important is at stake here. Hovering in a side street she would never have walked when alive, she watches the artistic striving of a child she might not otherwise have met, and once again Elizabeth thinks, How thrilling to be dead.

More silence. You still have nothing to say? Are you even listening?

You must be. So let’s see what you think about this ghost story:

Jake finds a love of snow, if only briefly, in the afterlife.

Before his heart clocked him out, he hated the stuff. Though snow caused accidents, and accidents brought extra work to his garage, his dislike went back to his days as a teenager. He’d been walking through a field after a snowfall, one of those necessary walks that took him from the chaos of home, when a tingling at the back of his neck had stopped him. He turned to face a line of footprints. Of course they were his own, but with a growing sense of horror he imagined being stalked by an invisible part of himself. Jake ran, even if he had no chance to escape those prints, and when he finally reached a side street cleared of snow, he had to gasp for air.

For the rest of his life he was the first in the neighborhood out the door after a snowfall, digging at the damned drifts until he scraped the sidewalk. Even after he shoveled it out of the way, he hated the piles that passing cars and sunlight turned into a dirty mess, as if the snow mocked his mechanic’s hands hidden inside his gloves, hands lined with threads of grime from work, dirt that he could never completely remove.

Soon after the start of his afterlife, Jake finds himself unable to resist floating through a patch of trees. He never thought much about trees during his life, so why do these matter to him now? He doesn’t know their names, never has, but their exposed winter branches look like a road system, a map to who-knows-where. Snow begins falling, his first snow as a ghost. The flakes tumble through him, and at first Jake thinks, They’re invading my privacy! He could easily fly away and escape, and hell, even if he ran away over the snow he’d leave no tracks. But he doesn’t move, he can’t move, because the snow swirling through him feels like a strange traffic. He has become an intersection, and he concentrates on individual flakes, on the beauty of their designs. The more Jake thinks about the whirling snow inside him, the less he has to think about anything else.

Still so quiet.

You’re a terrible audience.

It’s been . . . what?—an hour, maybe two, since you trapped me, and somehow imprisoned me? You hold me against my will, and still you won’t say a word, won’t explain your intentions, won’t bother to introduce yourself. Who are you?

More silence.

I wonder, do I reveal now that I know something—an unusual little something—about you, or should I be more careful and bide my time?

Again, you won’t speak. Aren’t you curious?

I know the power—and the consequences—of quiet. But I can’t let your silence unnerve me, I can’t. Instead, I’ll keep filling it up with stories. These little tales you’ve just heard? They’re snippets, only the coming attractions of what I can say.

We have time for another story, and another, don’t we? The afterlife, as you know, is so long.

This time, the ghost story is mine.

My name is Jenny. Last name—who cares? Ditto my date of birth—probably something-something 1980. I never quite made it to my third birthday, I never collected a dime from the Tooth Fairy. I’d be nineteen today if I hadn’t died, and not the hundreds of years I’ve managed to gather as a ghost.

I’ll start with my last morning alive. My mother had scolded me yet again for playing with my food, her weary voice sparking in me a familiar and irresistible stubbornness. I wasn’t much of a talker then, if you can believe it. Putting sentences together was still a struggle. I kept it simple: “Down! Down!”

I was too old to be locked in a high chair, and I kicked and kicked my legs. If my father had been home, he would have let me out long ago. But I knew another way to get out. For the second time that morning, I swept my arm across the tray, thrilling to the crash of the plastic plate and sippy-cup on the floor.

For the second time my mother knelt down and picked up the mess, carrot by carrot by pea. She could have used a dustpan and broom for a quick sweep, but I can see now that my mother needed a little calming down time before the next battle in our lunchtime war. Her patient hands never squeezed a pea or tiny cube of carrot too harshly before stowing them in the palm of her hand, as if they were bits of her anger she needed to control, as if she were trying to work out what to do about our stalemate.

How long she took. I watched her scoop up a pea and then a carrot, then a carrot and a pea. I found myself trying to guess what she’d do next. Two peas, and then two carrots? Or, carrot pea carrot? Or carrot carrot carrot? It took me years into my afterlife to recognize the secret gift my mother’s ritual gave me, the method that helped me hold myself together. The nub of everything I would eventually become.

When my mother finally stood, I braced for our next round. To my surprise, with her free hand she unclipped me from the high chair. I ran off before she could change her mind or remember she hadn’t wiped a wet napkin across my face.

By the time I climbed the stairs to the second floor, she still hadn’t called me back. Of course, I’d ignore her if she did. But I couldn’t ignore her quiet. How could she have forgotten me?

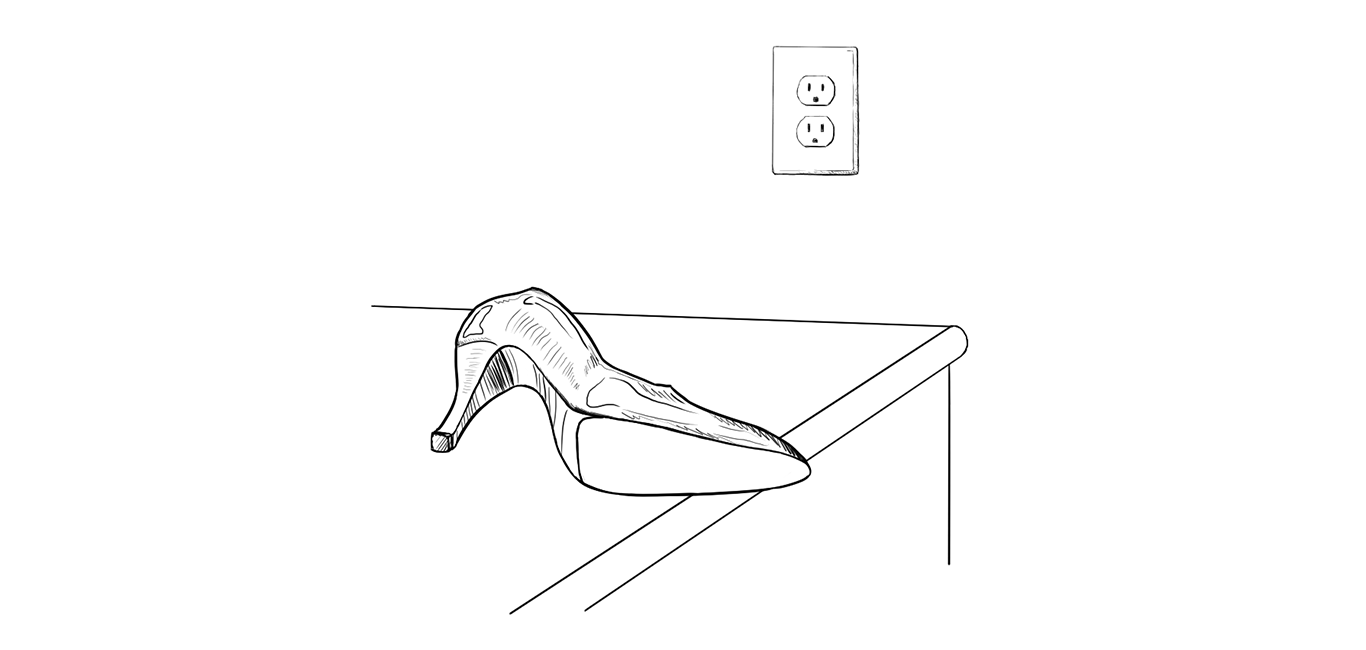

We’d see about that. All I had to do was hide, and soon enough she’d have to find me. I made my way to her closet in the big bedroom, to her pair of black high-heeled shoes. If I leaned in close enough, my face and dark curls appeared on the shiny surface. I shook those curls back and forth and watched them quiver. My mother’s wavy hair was no match for mine.

Still no sign of her.

I thought, Come, willing her to appear. Lately, I’d begun to suspect I did not really have this power. So I wanted it even more.

I fit my feet into those marvelous shoes and wobbled from the bedroom. Playing the big girl might coax a grudging smile from my mother or even make her laugh. Cute was another word I knew, and I knew how to use it. I could make us friends again.

The top of the stairs served as a stage, and I waited for any hint of footsteps. Nothing, not even the sound of water running or plates washing in the kitchen. Where had my mother disappeared? I was too young to imagine her enjoying a rare quiet moment, lingering by the living room window and staring outside, or sitting in a chair, eyes closed, thinking thoughts that were hers alone.

Again I thought, Come. I leaned forward, to better hear the slightest sign of her.

Nothing.

And again, I thought, Come.

As I said, I was stubborn. Still am.

You might want to reflect upon that.

Stubborn, but not nearly as patient as I should have been. I decided to find her instead. Forgetting where I stood, I raised my foot to take a first step.

More than once I’ve wished I could go back in time and whisper, “Keep away from the stairs, get out of those shoes.” Yet if I erased my death I’d also erase my afterlife. Saving that distant child I once was would be a kind of suicide.

I took that first step. And slipped. And fell. Down the stairs I tumbled, to the wooden floor below and the quick death of a cracked skull.

And that was that. No grand finale. Merely my own simple ending. The little ghost of me rushed out in startled recoil, and I shot into the air, up through one ceiling and then through another as if they were made of nothing, into the attic’s crawl space.

Do you remember your own death? Of course you do, even if you won’t answer my question. Because how could any of us forget? That moment is as individual as a fingerprint.

My three-year-old self had no word for what had happened. Yet I could see what I had somehow become. My invisibility was not invisible to me. I hovered in the air as a wispy, weightless thing with fluid borders, a shapeless cloud held together by the gravitational pull of my memories. Like all the other ghosts I’ve ever known, I’d become nothing but thought.

It takes some getting used to, doesn’t it?

Of all the memories revolving inside me, the shock of my fall was one that I couldn’t bear to face. So I turned further inward, one memory after another, to hide from that hurt.

My first stop was the afternoon when I’d toddled in the backyard to a corner garden. I’d only recently advanced past my first shaky steps, and the pleasure of the grass beneath my bare feet, the epic triumph of that short journey convinced me those flowers now belonged to me. An insect hovering above the petals of one of my new possessions was an outrage. I stepped on the creature, and that’s how I learned that bees can sting.

This memory morphed into my parents’ comfort in the kitchen as the pain bloomed in my foot. I burrowed into my father’s shoulder, inhaled the lush scent of his dark hair, and felt my mother’s fingers stroking my wet cheeks and lips. That’s how I discovered even bitter tears can taste delicious.

Then another teary moment offered itself, when I cried because my favorite doll, the one with dark liquid eyes, refused to speak—though she had a perfectly fine mouth. Those tears were an acceptable comfort.

How easily bad turned to good, or good to bad, the welcome warmth of a blanket during a nap altering at night to a disturbing clinging thing. Or how that strange object my parents loved talking to turned wondrous when my father held it to my ear and a voice inside spoke my name.

I floated in the attic, picking up these peas and carrots of myself, exploring greedily, returning to me the life I still didn’t know I’d lost: resisting the temptation to touch a glowing burner on the stove, splashing in the bathtub, running in circles just because I could. Then there were those mornings when I’d wake to a quiet house and, lying in my crib, softly babble a melody I made up as I went along. But if I woke instead to the distant sounds of my parents already busy in the kitchen, I howled and thrashed about until one of them released me.

I knew how to get out of a crib. I knew how to get out of a highchair.

And whoever you are, I will find a way to get out of you.

Eventually I lingered at only favorite memories and relived them once or twice or more before moving on, a budding form of power that delighted me. The afterlife can be a pretty good place for a toddler—finally I was the center of the universe. I wished, and it was done. My parents appeared or disappeared whenever I wanted. I ate only ice cream, crispy bacon, corn freshly scraped off a cob, and I banished from my sight dry crackers or runny eggs. If bathtub soap stung my eyes, I switched to the moment my mother dabbed them dry. I reduced a day of fever to a soothing cold cloth on my forehead. My trips to the potty? Only those with happy endings. My father used to disappear to someplace called “work,” an absence of endless hours until his return, but now I wished him home and there he stood, his grin as good as the hug he bent down to give me. Those first three years of life the living can’t remember? I made them my playground. I grew so skilled in pushing aside memories of hurt and frustration that I might have spent my entire afterlife believing I was an all-powerful little girl.

All perfect times come to an end. Mine ended in the middle of a favorite memory: sitting on the living room rug with my pile of soft blocks while my mother and father sat together on the couch. I listened to their quiet voices. Some words I knew, though most of what they said was beyond me. I waited for any new word that might make sense. When this happened, I gave whatever soft block I held an especially pleased squeeze.

I’m sure my parents didn’t know I was attempting to cross the border of putting words together into a full sentence and fitting further into their world. They were simply relieved I played beside them without demanding attention.

My first ghost, Willa, would expand my vocabulary later—but I’m getting way ahead of my story.

Then my parents’ voices changed, harsh tones I’d never heard from them before. I closed my eyes and wished their voices to be happy with each other again. But for once my powers failed me. Their voices seethed with suppressed rage: “Why don’t you—” “Not now—” “You’re always—“

The shouting seemed to come from the floor below me. I looked down—at wooden slats, not a living room rug. My blocks had vanished, the couch and my parents too.

Where was I? A place I’d caught a glimpse of only once, with my father when he searched among a stack of shadowy boxes. The attic.

Now, I floated alone in air sparkling with dust motes. I willed my parents to return, willed this awful attic to disappear. Nothing changed. I cried out in fear, but my voice carried less than a whisper. Who could hear such a voice? I tried again, nearly howling, my voice still no louder, and no one came. I stamped at the floor but I had no feet, no legs, just invisible parts of me that bent and wriggled into strange shapes. I may have reigned as the most powerful toddler in history, but I’d floated so long as a kind of cloud that I’d forgotten how to shape myself into the body I once had. Still, the force of that attempted pounding sank me through the floorboards, down through one ceiling and then another, sifting me through those solid barriers down to the living room, just in time to see my mother and father pushing a stroller out the front door.

How could they leave without me? I wobbled in the air after my parents, my impossibly silent voice calling their names, and after they closed the front door behind them I barreled through it.

They stood by the car parked in the driveway, and I wailed I’m sorry, as if becoming invisible was my fault. Then my mother pulled a drowsy girl from the stroller.

A girl who must be me. I’d been knocked out of my body, and there it was! I only had to slip back in. But those muscles and bones resisted all my efforts to return, and I noticed this girl’s hair was too curly, her eyes a darker brown, her lips thinner.

By now my father had settled in the driver’s seat. My mother, securing that mystery girl in a car seat, cooed, “There you go, Ellie.”

What happened to my name?

When I do the math now, it’s clear I’d floated in the attic long enough for my parents to have another child, but I understood none of that then.

Everything seemed the same, yet everything had changed. My parents arguing in the front seats looked like my parents but didn’t behave like them, their voices unusually cruel. I was locked out of my body, and my name was somehow “Ellie.”

Stop! I shouted. Stop! No one listened, my loss of control complete. Even now, I can barely speak of my confusion and terror. Like the living, every ghost I’ve met has a memory they can’t bear to return to.

What memory of yours fills that role?

My father put the car in reverse, and off we drove. We were headed for the mall, though I didn’t know that, any more than I knew I would find Willa there, or that years would pass before I saw my home again.

•

At the mall, I struggled to keep up, my airy body coiling and uncoiling like some invisible octopus or squid. Other invisible people mingled among the crowds of shoppers, but they looked nothing like me—their arms and legs were shaped like everyone else’s. Why was I so different?

Halfway down the mall’s broad hallway, a small circle of people faced a man with a top hat, and my parents eased the stroller closer.

“A bird!” the man shouted, holding an oddly-shaped balloon over his head, and then I saw possible wings, a tail, a rounded beak. He handed it to a lucky child.

As the crowd applauded, he stretched a narrow green balloon, inhaled, and blew it as far as it could go. When he tucked and twisted it into a shape he called a frog, that’s what it became. He delivered it to another eager child. His remarkable hands fit each squeaking balloon into legs and arms, making a giraffe, a monkey, a dog. I watched carefully, thinking if I echoed his movements I might control my shifting, fluid body. Every shape I tried unraveled.

Finally, the man said, “Thank you, thank you,” waved his hat, and packed up his trunk. That Ellie still stretched out her arms. She wanted a balloon too, and she wailed in the stroller as my parents pushed on down the hall. When they reached the mall’s central fountain, my father lifted her with an exasperated grunt.

As if I knew that fountain would soon transform my afterlife, I drew closer, wanting to get near the restless water that seemed like me, those water spouts that rose and fell into a stew of bubbles. For a moment, I forgot my family.

Then a shiny something flew through me, hit the water’s surface and sank. Father laughed, and I turned in time to see him hand the Ellie a coin. “Your turn,” he said. “Throw! For good luck.”

She tossed the penny in a quick arc, laughed when it hit the water and disappeared. She held out her hand for more. “Guh luck!” she shouted. Whatever that was, I wanted some too.

Another coin in hand, Ellie scrambled onto the fountain’s edge, just out of my father’s reach, and Mother shouted, “Pete, be careful, if she—”

Too late. Ellie tottered on the rim’s slick surface and slipped, tumbling face first into the water. Mother leapt in after her.

Again, I didn’t understand what unfolded before me. Ellie was in no danger of drowning in such shallow water, but Mother needed to believe she could rescue her child. Without hesitation, I plunged in too, foolishly hoping my mother would finally see and save me as well. But already she hauled Ellie, coughing and crying, out of the water, leaving me behind to watch through the waves their rippling figures. I couldn’t have felt more abandoned.

Though the water settled, I still sensed movement. I wasn’t alone. A transparent figure floated above the scattered coins at the bottom of the fountain and stared at them with strange intensity. Then she turned that gaze on me, her eyes widening with unspoken questions. Finally, finally, someone saw me, and nothing could stop my rushing through the water, nothing could stop my wanting to be held, and to hold.

And now it’s time for me to tell you the story of Willa.

What Jenny Could Have Said (but didn't)

Whoever you are, there are many stories that I can and will tell you, so many, but there are also certain moments of my life and afterlife that I will only think, instead. You will not hear those words. I will let them match your silence with silence. Just as I’m now only thinking this confession: I can’t risk exposing any secret that might be used against me. If only it were that simple! Because when I do speak, will I know enough of myself to recognize what reveals weakness, what reveals hidden power? In what ways should I confuse or unsettle you?

For the moment, I will keep unspoken my absolute refusal—even as a toddler in the infancy of my afterlife—to ever give up. So when that Balloon Man in the mall twisted his collection of balloons into animal shapes, I floated before him as light as air and kept trying, and failing, to imitate him. The cloud of me had nothing like a balloon’s firm edge.

Then he stretched a long yellow balloon, announced in a bored voice, “A cat,” and I worried that this animal might be his last performance—and my last chance! So when he inhaled deeply, I decided to hover before his lips.

He released his breath—smelling of pizza and cigarette smoke—and pushed me into the balloon as it expanded into a longer, wider shape. He tied a knot at the front, and I was safely inside, looking out at my parents and the rest of the crowd, everyone tinted yellow.

His hands set to work, the pressure of his fingers squeezing and knotting the balloon into separate sections, squeezing me into the bubbles that formed the ears, and then a head, a neck, and four legs.

And I became a yellow cat, for all to see. But when the Balloon Man eyed the crowd, I knew he was about to give me to some family that would take me to their home, not mine. Or worse, he might give me to that Ellie. How could I let that girl, who might be me, make me her toy? No! I was myself, Jenny, and I slipped from the comforting restraint of that balloon shape and returned to being an unpredictable invisible cloud.

Later, I swam no better in the mall’s fountain than I’d floated in the air, though the water contained my uncertain body with slightly greater force. Maybe my brief adventure as a balloon cat had taught me a first lesson on how to shape myself, because I floated, however awkwardly, toward another crucial moment of my afterlife: the discovery of someone like me in the fountain.

Yet never again would I be only Jenny.